Behind Rwanda’s elections

By Andrew M. Mwenda

KAMPALA – President Paul Kagame of Rwanda won re-election with 99.18% of the vote. Over 98% of the registered voters turned out to cast their ballot. I was in Rwanda with friends from Uganda who had come to witness the campaigns. They were amazed at the level of organization. The campaigns were festivals, balloting a form of celebration. Rwandans walked or drove from their homes in massive numbers to go to the polling station and vote. My Ugandan friends were amazed at the level of mass civic consciousness Rwandans exhibited in their enthusiasm for voting.

There are tall tales in sections of the anti-Rwanda coalition in Uganda and the rest of the world that soldiers move around villages with canes whipping people to go and vote. Yet what is missing during Rwanda’s polling day is a heavy presence of security that is common in our part of the world on voting day. Over the last 30 years, the Rwanda Patriotic Front (RPF) has actively cultivated a culture of solidarity among Rwandans. My friends were amazed to see volunteers drive elderly people, or those with disabilities to the polling station and help them vote. Even people admitted in hospitals voted because polling stations were organized nearby to ensure that.

Then there was voting of Rwandans in the diaspora. Over 80 polling stations were open in over 60 countries where Rwandans voted, one of them in Kampala. Again, voter turnout was high, and Kagame got over 95% of the vote of these diaspora Rwandans. The behavior of Rwandans in the diaspora drives the last nail in the propaganda that Rwandans inside the country are forced to show up and vote, or that ballot boxes are stuffed for Kagame. If Rwandans inside the country are intimidated, what of those abroad? Does Rwandan security apparatus move around precincts in Boston or London or Paris whipping Rwandans to go to the polling area to vote Kagame?

For most people, this seems too good to be true. Seeing the size of the voter turnout and the share of the vote Kagame got, people find easy explanations. They say such numbers were common during the time of Sadam Hussein in Iraq, Hosni Mubarak in Egypt, or even Juvenal Habyarimana in Rwanda. They say that those guys were dictators who used to get over 98% of the vote. How did this work? These presidents did not allow fair competition (whatever that means) and bulldozed citizens to vote for them. Based on this analogy, people then conclude that the elections in Rwanda in 2024 must therefore be like those of Sadam in Iraq.

By one stroke, Rwanda’s actual circumstances, context and history are written away. Such “experts” do not care about the facts, they care about the similarities in outcomes. But let us follow such an approach of analogy making to make sense of any other election. In 1984, President Ronald Reagan won every state except Massachusetts in the USA – over 90% of the electoral college. Would these “experts” therefore conclude, without looking at the circumstances, that he was Sadam? But such analogies that go for analysis are common when it comes to Rwanda.

I wrote in this column two weeks ago predicting that Kagame would get more than 99% of the vote. Why? Because anyone conversant with what has been happening in Rwanda would not be surprised by this. That country has gone through a transformation that is difficult to digest and that is the reason I pity (not condemn) those who make these wild analogies. Rwanda has been going through a rebirth, a reawakening, a new dawn. There is a lot of work that has gone into the ideological and spiritual rebirth of Rwanda. A country and a people that had been torn asunder only 30 years ago, have reorganized to see themselves differently.

When you visit Rwanda, a small and very poor country, one is amazed at the quality of their public infrastructure – roads, hospitals, schools, public gardens, police stations, army barracks etc. Rwandans tend to their country’s public spaces better than most humans tend to their homes. Visitors wonder how it is possible for people to be so dedicated to public services. The physical results of good roads, public gardens, pedestrian sidewalks, etc. are external manifestations of something much deeper and spiritual that has taken place in the Rwandan psyche. It is the cultivation of the idea that “ndi’omunyarwanda, ndafite agaciro, ndafite obudasa” (I am a Rwandan and I have dignity and I am unique).

No country has been involved in the ideological reawakening of its people as post genocide Rwanda has done. And this is understandable because the genocide in Rwanda was unique. As I have written before, although it was organized by the state, it was executed by society. Hence it was up-close and personal: father killed son, husband killed wife, house help killed his master, doctor killed patient, priest killed parishioner, neighbor killed neighbor and friend killed friend. How does one rebuild a society that has been torn asunder to such a degree? We do not have any other such experience in human history. What post genocide Rwanda has done, and the success with which they have done it, is a human miracle without precedent in history.

Kagame personally and the RPF generally have invested everything at creating this idea that Rwandans are one people with a common history and a shared destiny. That the project of rebuilding this country is a collective effort; failure of which would lead to shared catastrophe. So, Rwandans understand that they are all in it together and shall swim and sink together. This idea of a shared destiny has created unity of purpose. Rwandans do not see elections as a contest among different alternatives on who should take power. Rather they see it as an effort to create a unified power; a power that can harness the collective aspirations of all Rwandans into a purposeful project of national economic and social transformation.

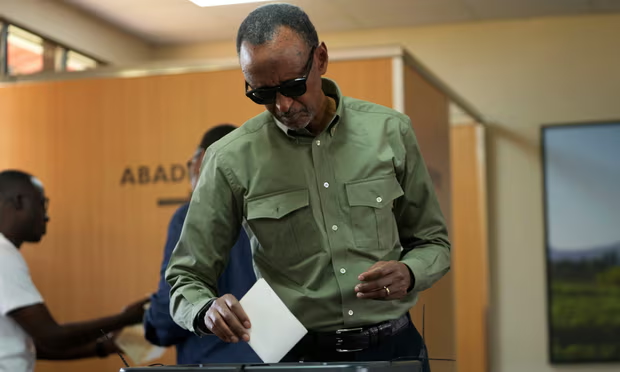

Kagame is seen by the vast majority of Rwandans as representing this collective aspiration. His rallies were like festivals. He didn’t even campaign. He came to join other Rwandans to celebrate the miraculous recovery of their country. On polling day, Rwandans did not go to vote. At every polling station, people came to celebrate their good fortune. That is why voting was a collective enterprise with volunteers ferrying the old, weak and disabled to the booth. It was an expression of the Rwanda they want to see.